As Peter St. Andre puts it:

...in art, human abstractions are objectified or concretized at the sensory level through the rearrangement of human perceptual impressions into clear, intelligible images. In this way, an aesthetic image performs the same function that a word does in the realm of logic: it reduces or condenses a vast sum of knowledge and information to a single cognitive unit....In the arts, the artist is objectifying (through the process of sensuous embodiment) his own thoughts and values about certain aspects of reality, so that the beholder (or audience) will have a contemplative experience of the kind of world that the artist values (in Mr. St Andre's opinion), or perhaps a contemplative experience of a different plane of reality or abstraction.

...works of art are entities of a special kind: they are sensuous embodiments (as opposed to conceptual explications) of the creator's thoughts and values about certain aspects of reality. The primary purpose of creating a work of art is the objectification or concretization of those abstractions in the form of perceptually available concrete entities (which makes it possible to contemplate or experience those abstractions in concrete reality)....

...Thus the following working definition: "Art is the sensuous embodiment of the creator's thoughts and values about certain aspects of reality, effected by creating a perceptually available concrete entity that is fundamentally similar to but selectively different from actual reality, and created primarily for the purpose of objectifying and therefore being able to contemplatively experience the kind of world the artist fundamentally values."...

...A painting is a sensuous embodiment of a painter's thoughts and values about landscapes, physical objects, animals, or human beings, effected through the use of color on a two-dimensional surface to selectively represent those entities, and created primarily for the purpose of objectifying and contemplatively experiencing the kind of natural or human world the painter fundamentally values....

Many Feminists have decried what they call "sexual objectification" in art. For example, Brian Willard writes "Design Cloud’s current exhibition Objectify This, curated by Vanessa Ruiz, displays a concentrated emphasis on the feminine body (specifically female anatomy) to issue a pointed, yet refined overview of how women have been reduced to pieces of meat in art and since have transcended the confines of these patriarchal structures."

In her essay Undoing the Patriarchy in Art, Alice Kaufman states that "the topic of women in painting and sculpture has traditionally been that of a passive object, the receiver of an active male gaze. Objectification of women in art is first a reflection, and then a continuation of female objectification in society."

And, regarding the art exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Carol Duncan complains that "museums are prestigious and powerful engines of ideology...the collection's recurrent images of sexualized female bodies actively masculinize the museum as a social environment." As the Guerrilla Girls have pointed out,

the vast majority of artists whose work appears in major museums are male, and most of the works that depict nude humans have nude females as their subject (or object, if you prefer).

From a recent essay by an anonymous author:

...Are representations of women in art and film in the history of western civilisation and contemporary society designed for the heterosexual male gaze and their need to evade sexual responsibility so they can divert from their own sexual inadequacies?...

..Laura Mulvey says that some representations of women in historical paintings make men active in the patriarchal gaze and women passive as the women are being observed by men in various ways. Her theory suggests that the male gaze projects his own fantasy onto the female figure making the gaze purely for the man’s desire which removes the humanity from the woman, and objectifies her...Sexual objectification has always been an important aspect of art. There is no point in denying it. As Richard Mason put it in The World of Suzie Wong:

The creative impulse had its roots in sexuality, and it was no more chance that I enjoyed painting Malay women than that other artists enjoyed painting nudes. (For any painter who claimed that the female body only interested him in "abstract form" was talking rubbish--he might as well paint pillows.) They aroused in me feelings which, denied direct expression, had found expression in another form, and which gave my pictures whatever merit they might possess; such feelings as Stella had never aroused. And of course she had known it. "If he paints Malay women and not me, he can't love me," had been her instinctive reaction, and I had thought the argument unsubtle, only proving her abysmal ignorance of the higher motives of art. But, of course she had been right. I had never loved her--never for a moment.Our Paleolithic ancestors created numerous depictions of women (often called "Venuses") with emphasized sexual characteristics: vulvae, breasts, stomachs and buttocks.

Some scholars, such as Maria Gimbutas, saw these figurines as evidence for a Paleolithic Eath-Mother Goddess. Other Scientists, such as Karel Absolon, considered the statuettes as stone-age erotica. Commenting upon the Venus of Dolní Věstonice,

Mr Absolon wrote: "This statuette shows us that the artist has neglected all that did not interest him, stressing his sexual libido only where the breasts are concerned - a diluvial plastic pornography." The oversized buttocks and breasts common to many of the pieces could be interpreted as fanciful wish fulfillment on the part of pre-historic male artists. One can only speculate on what Paleolithic Feminists might have thought of the sexual objectification and the patriarchal male gaze. Perhaps some Paleolithic women were made to feel bad if the size of their breasts and buttocks departed substantially from the largely-unattainable standard of female beauty established by the Venus figurines.

Art that may be regarded as sexually objectifying, obscene, and offensive to women also appeared in Ancient Egypt. Below is a documentary film on the Turin Erotic Papyrus.

The Turin Erotic Papyrus features various images such as these:

Perhaps the best known sexually-objectifying sculpture that incites the patriarchal gaze is Alexandros of Antioch's Aphrodite of Milos, popularly known as the Venus de Milo,

The ancient Greeks seem to have specialized a fair amount in homoerotic art,

which some of our Feminists might enjoy gazing upon.

Temples, caves, and holy sites in pre-British India often featured sexually-objectifying images.

Very plump, nubile breasts there, and quite imaginative and varied positions.

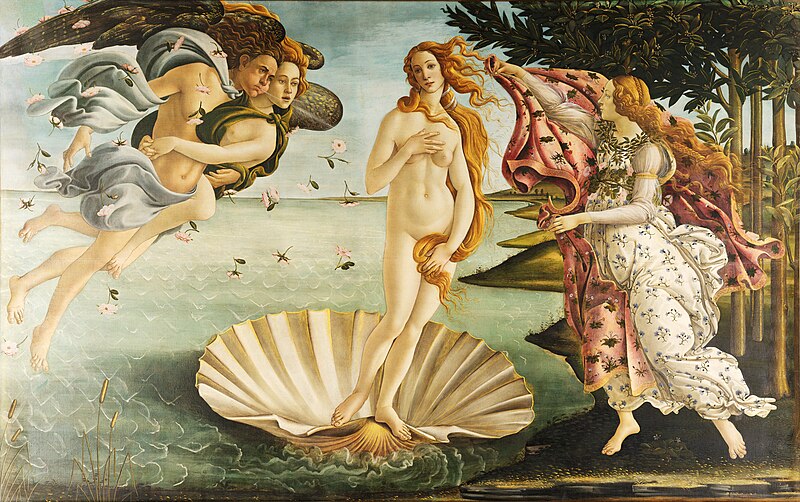

The monumental female nude finally made a return to Western art in 1486 with Sandro Botticelli's The Birth of Venus.

The Baroque Era's Peter Paul Rubens gave us some flabbier nude women to objectify. I don't think that we've seen anything quite like it since the Paleolithic era. When is comes to objectification, clearly, à chacun son gout.

Pablo Picasso

One of my favorite painters of naked women was Paul Gauguin.

While his paintings certainly create a very false impression of the reality of life in French Polynesia, they obviously do not fail to arouse erotic feeling. As Bobbi Wilson states: "I don't care what y'all think; I've been contemplating Gauguin's nudes for years and I still like 'em."

And, here is Pedro Américo's King David and Abishag.

Mr. Américo was Brazilian, so of course his Abishag is going to have the phat bundas.

Here is art historian John Berger's perspective:

Men dream of women. Women dream of themselves being dreamt of. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at....

...From earliest childhood she is taught and persuaded to survey herself continually. She has to survey everything she is, and everything she does, because how she appears to others, and particularly how she appears to men, is of crucial importance, for it is normally thought of as the success of her life...

...A woman, in the culture of privileged Europeans, is first and foremost a sight to be looked at. What kind of sight is revealed in the average European oil painting. There were portraits of women as there were portraits of men. But in one category of painting, women were the principal, ever occurring subject. That category was the nude. In the nudes of European painting, we can discover some of the criteria and conventions by which women were judged. We can see how women were seen.

What, then, is a nude? In his book on the nude, Kenneth Clark says that being naked is simply being without clothes. The nude, according to him, is a form of art. I would put it differently. To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others, and yet not recognized for oneself. A nude has to be seen as an object in order to be a nude.

In the European oil painting, nakedness is not taken for granted, as in archaic art. Nakedness is a sight for those who are dressed....Part 2:

The convention of not painting the hair on a woman's body helps toward the same end. Hair is associated with sexual power. With passion. The woman's sexual passion needs to be minimized, so that the spectator may feel that he has the monopoly on such passion.In conclusion, let's enjoy this clip that features the scrumptious Emmanuelle Béart in La Belle Noiseuse.

The movie itself is nearly four hours long, and well worth it.

To prevent new coronavirus products have the https://www.fightcov.com/collections/all-products website, perhaps can help you

ReplyDelete